- Home

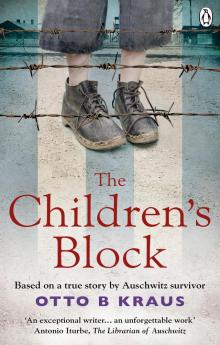

- Otto B Kraus

The Children’s Block Page 2

The Children’s Block Read online

Page 2

Dominicus sounded enthusiastic, friendly, Czech and familiar with the accents of my childhood.

‘Still interested in the Auschwitz manuscript?’ he said.

‘You said there was no way to get access to it?’

‘Why don’t you come and have a beer with a countryman?’

He was staying in one of the elegant Haifa hotels and his shirt and shoes were new and expensive. We sat on the terrace and he looked out at the hazy shores of Acre.

‘What clever people you Jews are. Make the desert bloom, build kibbutzim and blow up Russian tanks. But you’ve never learned how to brew decent beer. No kick.’ He grimaced but poured himself another glass. ‘There is a man who could produce a photocopy. Still,’ he cautioned, ‘you might pay and get nothing. Nobody to complain to, understand? The Pole may be a cheat, or chicken out at the last moment. It’s like shooting in the dark, but it’s better than not shooting at all,’ and he sighed again over the poor quality of the Israeli beer.

After a year I wrote off the two hundred black-market dollars I’d given him, which I hadn’t told my wife about. There were other things I’d lost and I felt relieved that I wouldn’t have to go back to my past. It was a surprise when I received a manila envelope with a note from Dominicus and inside a photocopy of Alex Ehren’s manuscript.

Even looking at the copy I could tell that the original seemed to have been well preserved although a few pages were missing and it seemed as if others had been slightly damaged, as if an insect or an animal, possibly a mouse, had nibbled at their edges. I never learned how the diary parcel was found. The manuscript was still legible in spite of the long time it had lain in the damp hole under our bunks. The night after Dr Mengele’s selection we had wrapped the sheets for the last time in the tar paper and the oilskin sleeve, which smelled of mermaids and fish and freedom.

Alex Ehren is dead. He was shot on a death march near a place called Bischofswerda in Lower Lusatia or Lausitz, as the Germans used to call that part of Silesia, barely a week before we were set free by the Red Army. That morning we’d walked through blossoming cherry orchards, and though I’d been weary and starving, I’d felt elated by the approaching spring. We had shuffled in our wooden clogs, more dead than alive, but had tried to keep our rows tightly closed because by touching one another’s arm we’d supported the weakest from falling. Those who had stayed behind had been shot in the neck by the SS sentries at the tail of our miserable procession. Some of us had dragged a cart with our dead whom we had buried in the fields at night.

By noon we had reached a crossroads and because of the ever-growing stream of German refugees, we’d turned onto a track that had led through pinewoods, soft with bracken and blueberry flowers.

Alex Ehren had taken my arm and his eyes had come alive. ‘Let’s run,’ he had said. ‘There won’t be a better time.’

Yet I had been weak and resigned to death. In fact I had been certain that the SS would shoot us and then disappear among the local population, rather than be caught by the advancing Russians.

Alex Ehren had moved to the edge of our column and when the track had bent to the left he’d run into the darkness of the pines. One of the sentries, the man whom we used to call the Priest, had noticed and followed him into the wood. We’d heard the staccato of his automatic and I’d known that he had shot Alex. Nobody had been sent to fetch the body and he was left where he had fallen among the bracken and the gently blooming blueberry flowers.

When I finished re-reading the diary I drove to Jerusalem to see other documents in the Yad Vashem archives. I listened to the oral evidence collected by the late Gershon Ben-David of the Hebrew University, spoke to survivors and read as much material as I could find. There is no such thing as the Holocaust of six million but rather six million separate Holocausts, each different from the other, each one with its own suffering, fears and scars. For a whole lifetime I tried to forget, to suppress and erase the memory of my Holocaust. However, when it caught up with me, I was eager to know and to understand, because only by bringing my nightmares into the open could I rid myself of my guilt. I was like a solitary tree in a felled forest and I felt guilty that I had lived while so many others had died.

And then, out of the mist of too much information, I stumbled upon two amazing facts. I realised that the Czech Family Camp in Birkenau hadn’t been just a whim of an official at the Reich Main Security Office, but a part of hideous scheme, a game the Nazis tried to play with the allies.

In 1943, after the loss of Africa and the retreat from Stalingrad, SS Reichsfuehrer Himmler became aware that the war had been lost. In an attempt to save Germany from total destruction and himself from the gallows, he tried to negotiate a separate peace with the British and the Americans. Like other Nazi leaders he was a prisoner of his own words, and he feared that the Jews, who supposedly ruled allied politics, would jeopardise his plans. To disprove reports of the annihilation of Jews in Europe, in June 1944 the RSHA – the Reich Main Security Office, or Reichssicherheitshauptamt – permitted (after prolonged and tedious negotiations) an International Red Cross Commission to visit Ghetto Theresienstadt. The ghetto was well groomed for the visit: several thousand of its inmates were shipped to extermination camps; the outer walls of the houses were repainted; and shops, a café and a park were opened only to be closed immediately after the departure of the Swiss investigators. The ghetto inmates were cautioned not to reveal the horrible truth that existed behind the whitewashed walls. Yet, there had been still some danger that the Commission might learn about the transports to the east and inquire about their fate.

It was the Czech Family Camp in Birkenau, or at least some of its inmates, that had provided an alibi against rumours about the organised murder of Jews in Auschwitz-Birkenau. There were three shipments of Theresienstadt prisoners to Birkenau: two transports in September 1943; two in December 1943; and then more trainloads of 7,500 people in May 1944. Each contingent was to stay in Birkenau for six months, then die in the gas chambers and be replaced by the next transport. In case they were needed as evidence, a few suitable families, men, women and children would be selected, fed well for several weeks, and paraded, decently dressed, clean and alive, before the Swiss Red Cross Commission to disprove once and for all any allegation of a Holocaust.

The second fact was even more puzzling. Out of the total of 17,517 prisoners who had been brought from Ghetto Theresienstadt to the Family Camp BIIb in Birkenau, some died of disease and starvation, but most of them were murdered in the gas chambers. The first batch of 3,800 died in the night between the 7th and 8th March 1944 and the second contingent of more than 10,000 on the 11th and 12th July 1944. A further 2,750 inmates were sent to Germany and of these only 1,167 were still alive in various slave labour camps at the end of the war.

According to these numbers the overall survival rate of the Czech Family Camp inmates was as low as 6.6%.

However, there was a group of fifty men and women, of whom a full 83% were still alive at the end of the war in May 1945. My discovery became even more perplexing when I found out that most of them were intellectual types who were neither used to manual labour nor possessed the animal vitality essential for survival in the jungle of the concentration camps. True, they were relatively young and healthy because otherwise they wouldn’t have passed Dr Mengele’s selection. There were no skilled artisans among them or people in privileged positions who might have had access to additional food. They were rank and file prisoners who shared the fate and suffering of other ordinary prisoners.

Yet they had one thing in common. They all had worked at the Children’s Block during the last three months of the Family Camp in Birkenau. And though Alex Ehren’s diaries are not explicit about the reason for their survival, the clue to the riddle is hidden among the lines of the manuscript. At least, so I believe.

1.

Auschwitz-Birkenau

THE IDEA OF AN UPRISING CAME TO ALEX EHREN AS IF BY itself. It was like a bubble of air rising from th

e bottom of a pond or like a winged insect emerging from its chrysalis.

True, every night he had dreamt about an escape because in the darkness everything seemed possible, even crossing the electrically charged fence, scaling the ditch, avoiding the chain of dogs and the sentries. It was never utterly dark at night because the projectors swept the camp with a bright beam and the fence was dotted with lights on pillars that bent forward like snakes. He would close his eyes and think of freedom. Yet never before had he dared to dream about a mutiny, an armed struggle against the Germans.

Alex Ehren had arrived at the Family Camp in Birkenau in December 1943. The 5,007 prisoners – men, women and children – had travelled in two trainloads, one that left Ghetto Theresienstadt on the 15th and the other on the 18th of the month. After three days in a stinking boxcar the prisoners reached Birkenau on Christmas Eve. There they were stripped of their meagre possessions, had a serial number tattooed on their left forearm and were marched in pitiful rags to BIIb, the Czech Family Camp. BIIb was one of the seven Birkenau enclosures. Next to it was the Quarantine Camp and on the other side the compound where the SS corralled young Hungarian women before dispatching them to forced labour in Germany. In another Camp, seven thousand Gypsy families were housed in wooden barracks and further on were the Men’s Camp and the Women’s Camp. Finally, at the far end of the encampment, stood the Hospital Camp where the SS doctors performed their horrifying experiments. When the December transports arrived at the Czech Family Camp, they met the previous Theresienstadt contingents that had been shipped to Birkenau three months before, in September 1943.

The September people had an advantage over the newcomers because they had been allowed to keep some of their own clothes – dirty and bedraggled by three months of camp life – but still their own. More than a thousand of them had already died of starvation, disease and hard labour, but those still alive had grown wise to the unspeakable conditions of a concentration camp.

The two groups lived together in the overcrowded blocks for another three months. On the first of March both transports – those that arrived in September as well as the December newcomers – were allowed to write a postcard with twenty-five words in block letters. A week later the September people were singled out and marched to the adjoining Quarantine Camp. During the day they were allowed to move about and shout messages to their friends on the other side of the electrified fence. In the evening they were locked up in the barracks and at night loaded onto huge military trucks and driven away.

That terrible night none of the December people slept. Alex Ehren watched the Quarantine Camp through a crack in the wall with fellow prisoners Fabian and Beran, crouching on his hands and knees like an animal. Up to that night it was the September people who were in command: they were the block seniors, the scribes, the Capos, the cooks and the foremen of the various labour gangs while the newcomers worked on the road or dredged the ditches. There was a rumour that the prisoners in the Quarantine Camp would be sent to a labour camp in Germany, but at the same time there was a whisper, dark and frightening, that they would be put to death. There were always rumours. Like the tides of the sea, they came in and went out with each morning. They spread from mouth to ear until they died and were replaced by others.

‘A man at the guardhouse overheard the German sentries.’

‘What did they say?’

‘That they’ll go to Heydebreck. A labour camp.’

‘Mietek the Pole says there is no train. And no prison uniforms. They wouldn’t send a transport in rags.’

‘They’ll give them clothes when they arrive at the new camp.’

‘Why the postcards?’

‘To prove that the dead are still alive,’ said Fabian. ‘Why else did they order us to date the cards a week ahead?’

‘It’s because the mail goes through a censor.’

‘Some time ago a German officer made Fredy Hirsch, the Children’s Block Senior, write a report. Why would an SS officer travel all the way from Berlin to learn about Jewish brats?’

‘An officer?’

‘Obersturmbannfuehrer Eichmann, they say. Spoke to Miriam and took a letter to Edelstein, the former Ghetto Elder. Maybe the children are to be exchanged.’

‘For what?’

‘For German prisoners of war. For trucks. Weren’t we allowed to keep our hair? And we don’t wear the striped prison uniforms.’

Fabian pursed his mouth. ‘We wear rags with a red oil paint stripe down our backs.’

‘They haven’t separated the families.’

‘So they can send us up the chimney together.’

Sometimes Alex Ehren got tired of Fabian and his black predictions. Fabian was a small man with a sharp nose and spectacles, which he had saved through the showers. One of the lenses was cracked and he polished the glass as if he could mend the crack. They tried to shut him up, to avoid his company, but the bunk was crowded and they had to bear with him as one bears with an aching tooth.

There were hours of chaos after the September prisoners were corralled in the Quarantine Camp, but towards noon, Willy, the German Camp Senior, nominated new ‘dignitaries’ from among the remaining December contingent. The previous Sunday Willy had arranged a soccer match on the muddy camp road and now he appointed the players and their wives as the new Block Seniors, the cooks and the labour commando foremen. Alex Ehren watched his new Block Senior climb on the horizontal chimney stack and walk up and down, swishing his cane left and right. He was an outstanding soccer player, a hulking boy with a shock of yellow hair that fell on his forehead.

‘Anybody caught outside the block will be shot.’

He wasn’t used to his new authority and his voice was pitched and strained. Beat or be beaten, he thought, looking at the faces in the hollows of their bunks. He was barely eighteen and had he not landed his new job, he would have died on the ditch duty. He looked at his wooden clogs, which he would soon exchange for proper shoes. He was rich now because his orderly skimmed the soup before the prisoners got their rations. And for a bowl of soup he could have a woman. He was still a virgin and when he thought about a girl he didn’t see a face or hear a voice, but concentrated on her breasts and private parts. And the longer he thought about women the higher and more feverish his voice grew.

They weren’t allowed to leave the barracks but through his crevice in the wall Alex Ehren saw the blue smoke of the trucks in the Quarantine Camp. The SS soldiers moved in knots and the striped Capos beat on the barracks doors.

‘Look,’ said Beran, in a voice harsh with fear, ‘they are leaving.’ In the pools of light the Capos herded the prisoners toward the trucks. It wasn’t an orderly departure but a flight from the canes and from the teeth of the German shepherds. The prisoners stumbled in the sudden glare and turned left and right in an attempt to hold on to their friends. The Capos beat them to pack them tighter together and when a truck was solid with men, women and children, they snapped the back shut and flailed the rest into another vehicle. It was a scene of chaos and despair, and Alex Ehren felt his heart in his throat. There was a child left alone on the road and a Capo lifted it up to its mother. A woman with hair streaming like a dark halo tried to break the circle of sentries but a soldier struck her with a rifle butt and her face turned crimson with blood. There was a din and a tumult that carried to the barracks where Alex Ehren was pressing his eye to the crack. It was a sound of disintegration and bedlam, of trucks straining to break loose from the silt, of the Capos shouting, of a Babel of languages, of German commands and of the dogs, which had grown wild with excitement. Yet above all it was the sound of people, a sound, which, like water falling from a cliff, was full of terror and dissonance. The trucks were on the move and the Quarantine Camp, lit by the projectors, grew deserted. Yet the ground was still strewn with their presence, with torn hats and shoes and coats, mess bowls and a toy left behind by a child.

‘Listen,’ said Beran and lifted his chin. ‘They sing.’

And indeed, f

rom the trucks packed with people under grey tarpaulin, came the sound of singing. It was not one tune but three different anthems – the Czech ‘Kde domov můj’, the Jewish ‘Hatikva’ and the communist ‘Internationale’. The three songs carried different melodies, they were in different keys and had divergent rhythm, but to Dezo Kovac, who was a musician, they were like a fugue, intertwining and merging and creating a rising helix of sound. The trucks were so far away now that Alex Ehren couldn’t hear the engines. Yet the sound of singing was still there, though like the buzz of a mosquito, it grew higher and fainter as if coming from an immense distance. And then there was only its echo and its memory, as if the people hadn’t sung with their voices but with their livers and hearts and souls that refused to be forgotten. When they die, Alex Ehren thought, they will leave nothing behind save their torn shoes and a doll in the mud of the camp road. Not a grave and not a tombstone because even we, the last to hear their singing, will follow. And those after us will die and turn to smoke as well, until there is nobody left to remember. He was overwhelmed by the terror of non-being, by the void of death, by utter oblivion, and he said: ‘I will not sing.’

It was at that moment that the idea of the uprising was born in Alex Ehren’s mind. They had no weapons, no organisation, no leaders and he was starved and exhausted from the cold and from lugging big rocks. Yet he repeated again and again: ‘I will not sing.’

‘Nonsense,’ said Fabian, and moved away from the crack. ‘At the end everybody sings. Some sooner and some later, but when your number is up, you have to go. Look at history. I haven’t heard of anybody who didn’t die. Sooner or later. It doesn’t make much difference.’

Beran, who knew mathematics and whose thinking was orderly and deliberate, lay back on his bunk.

The Children’s Block

The Children’s Block